Regulation – the promised land?

At a time when it is now widely accepted we need to manage drugs differently, because the prohibition of particular drugs has caused more damage than the drugs the state was purported to be protecting us from, there is a risk drug reformers seize any offers of apparent positive change – without thinking more critically about what is on offer. After decades of frustration from the archaic criminalisation of possession of particular drugs, while other more dangerous legal drugs went under the radar, some level of drug reform now appears likely, and there is a rally call to unite under the the very broad umbrella of drug ‘regulation’ as the way ahead.

The main thrust of prioritising regulation appears to be we need to get the drug market out of the hands of the criminal underworld. I wouldn’t disagree with taking drugs out of the hands of gangsters, however, let’s be clear here, most damage suffered by people who use illicit drugs isn’t caused by the criminal underworld, most damage results from state criminalisation and policing. In the absence of strict state regulation the daily activity of growing, making, buying, selling and exchanging goods and services doesn’t inevitably drift into the hands of dangerous criminals who manage business with guns, knives and baseball bats, but extreme law enforcement measures and severe penalties, have created a hostile and violent environment within which a lucrative underground drug business must operates.

Why Decriminalisation?

The notion that decriminalisation, rather than regulation, as an initial first step would result in the illegal drug market entirely managed by gangsters is somewhat exaggerated. If we prioritised decriminalisation rather than strict state control (regulation) then cannabis, which is the drug most frequently used illicit drug and the one that occupies most police time, would largely be home grown, shared and exchanged by friends, local growers and societies. Other illicit drugs that are not easily ‘home grown’ could, in a more relaxed transitionary period of drug policy development, be more easily purchased via websites such as Silk Road that operate a consumer rating system, not dissimilar to TradeMe or Ebay. Not perfect, not properly regulated, but this can hardly be described as a threatening market ruled by violence, exploitation and gangsters. The present criminal sub-culture that surrounds the illicit drug market has much more to do with the environment created by fierce law enforcement and prohibition than any preferred pattern of operation by producers, buyers and sellers of drugs, and little to do with the product on sale.

Decriminalisation as a first step towards living with drugs would importantly protect users (particularly the poor, indigenous people and people of colour who are targeted by law enforcement agencies) from police stop and searches, drug related arrests, penalties and incarceration. Drug users would be free from the serious and life long damage of a drug conviction. This would provide more time to look critically and carefully at drug market regulation. The history of regulation involving legal substances alcohol and tobacco has not exactly inspired confidence. The recent significant increase in drug overdose deaths in the USA due largely to regulated painkilling drugs featured in the article below is a reminder of the serious problems that can arise – despite regulation.

The Carrot of Tackling Stigma

If multi-national corporations, and in the example above BigPharma, have unbridled control and extensive freedom to promote and distribute their commercial drug products, major problems can arise from the culture and patterns of drug use. In addition to highlighting the problem of fatal overdoses in the USA the article promotes the need to tackle the stigma of addiction. So after years of trying to combat stigma, discrimination and hostility towards people who use illicit drugs, drug reformers now have the support of the all-powerful USA to unite and push to remove stigma from addiction. An attractive proposition – how could we disagree with removing stigma, surely it’s a campaign worth joining? In and of itself, it certainly would be, but If we look closely, the momentum in the USA to remove stigma is strongly tied with a commitment to promote and embrace the abstinence based disease model of addiction – and the burgeoning rehab and drug testing industry associated with it.

This commitment to the disease and abstinence model has been reinforced by recent high profile appointments in the US drugs field of ‘recovering addicts’ such as Mr. Botticelli the Drug Czar, who will lead the campaign to end the stigma of addiction by pushing for a global adoption of the twelve steps disease model of addiction where the ‘sick’ will forever be in recovery and will be required to live a life of sobriety. No thanks. Like the US campaign to end stigma that has a worrying sting in the tail (promoting abstinence and the adoption of a disease model of addiction), the drive towards drug regulation may also contain some nasty surprises. Strict state regulation per se is a dangerous path to follow, much depends upon what state controls and punishments are imposed. The devil is in the detail and it seems somewhat strange to immediately place trust in the perpetrator to become the new arbitrator and designer of drug control regulations. Under the guise of protecting the individual from the potential harm of illicit drugs the paternalistic state has been trusted with powers over the sovereignty of what a person can consume in their own body. This trust has been misplaced, and these law enforcement powers have been woefully abused. The war on illicit drugs will be remembered with great shame and incredulity in history, and lessons should be learned from this breach of human rights.

New Zealand Psychoactive Substances Regulation

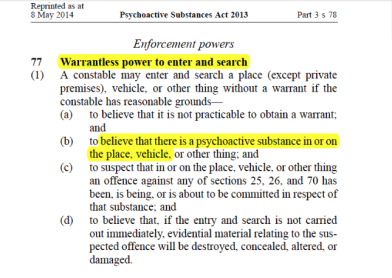

A worrying example of a regulatory model widely promoted by some drug reformers, is the New Zealand Psychoactive Substances Act 2013 which ‘regulated’ legal highs. Under this model, instead of all substances being legal to possess (unless specified and banned under the NZ Misuse of Drugs Act 1975), all psychoactive substances in New Zealand are now illegal to possess unless approved by the state and purchased from an approved commercial seller. In this model of regulation personal possession of any ‘unregulated’ psychoactive substance is an offence that carries a $500 fine, while supply of any unregulated substance is an offence that can lead to two years in prison. Doesn’t this sound a little like repackaged prohibition? The degree of perceived threat posed by unregulated psychoactive substances is such that in order to prevent unregulated supplies New Zealand police have been issued with new intrusive warrantless powers for substances that were previously legal:

What this regulatory model has effectively done is widen the net of prohibition, state control and punishment in New Zealand to include every new psychoactive substance. This raises further important questions regarding how we define what is a psychoactive substance.

After thirty years of working in the drugs field and seeing the terrible damage caused by the war on people who use illicit drugs, it is clear that more harm has been caused by drug policy than from drug use, and whatever regulatory model is eventually rolled out, the non-negotiable priority is that we must ensure personal possession is not an offence, civil or criminal. The individual must have the sovereign right over their own body to consume what they wish – without fear, threat or punishment from the state – the human right to choose. Regulations instead should be confined to market related issues such as production, distribution, sale and advertising and seek to protect the rights and freedom of the individual.

Out of the Frying Pan and into the Fire

A united drug reform campaign to end prohibition and stigma sounds like a dream ticket – but not if drug regulation provides the state with new powers to punish personal possession of unregulated substances, and not if combating stigma means enforcing abstinence and rolling out a the 12 step disease model of addiction – that’s akin to jumping out of the ‘frying pan into the fire’.

Hard fought campaigns for drug law change should not be squandered. For forty years the UK Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 and in New Zealand Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 have been impervious to any positive reform and this illustrates just how difficult it might be to make positive amendments to any new drug legislation. Whereas, punitive orientated amendments to drug laws have been much easier to achieve. Considerable caution should therefore be exercised before supporting any new drug laws.

This war between drugs (legal vs illegal) maintained by a relentless, oppressive and robust global drug apartheid, must collapse, like slavery, like the Berlin wall and the South African racial apartheid. The global human and environmental damage caused by the war on illegal drugs is comparable to these terrible historic injustices, and similarly the insidious legacy of propaganda, lies and prejudice will take many decades to dispel.

The legal drug industry profiteers realise support from the law enforcement regime of the drug apartheid is in its final chapter, and we observe a strategic shift and reconfiguration taking place to secure new civil controls through abstinence, drug testing and a disease model. As drug reformers we need to push for revolutionary reform at this critical moment in time, and demand a rational, evidenced based approach to drug policy with human rights and harm reduction at the centre. The campaign to end drug prohibition should not be dissipated by an invitation to cannabis to join the elite substances on the privileged and powerful side of the drug apartheid, nor by the offer to replace prohibition with strict state regulation that incorporates punishment for unapproved possession. No, tweaking or transforming the present corrupt model rooted in racism, self-interest and misinformation is not an option.

The Way Ahead?

The first and foremost change to reduce harm and restore human rights is to prioritise the decriminalisation of personal possession of all substances. Once the human right to possess and consume what an individual chooses with their own body is restored, without fear, threat or punishment from the state, then the complex and tricky road of developing appropriate drug market regulations can begin, but there are a number of potential threats to derail this much needed drug policy change as illustrated in the graphic above. Drug policy change is now possible and indeed likely, but we need to make sure the opportunity is not squandered or hijacked by drug reform entrepreneurs because it could be another four decades before the next opportunity arises.

by Julian Buchanan 7th October 2014

Julian Buchanan is Associate Professor at the Institute of Criminology, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand.

What are you concerned Big Business is going to do? Presumably they will want to promote the product and capture market share. They will target current users and try to promote it to future users and entice people to try it. In the U.S. isn’t maximizing shareholder wealth a contractual obligation when you incorporate. They would be obligated to.

Or do you think Big Pharma will want to take over the all the manufacture and distribution of every drug on the planet.

If money can be made, they will want as much of the profit as they can get. If we don’t do this legalization (and we should legalize drugs) of drugs very carefully we will have a very big problem, however, no matter how big it gets it will not be as big of a problem as the war on drugs has been.

LikeLike

Agreed

We need sensible and responsible regulation to control BigPharm and BigBusiness not to control the consumers

LikeLike

Marijuana Should Be Sold To Kids Like Chocolate Or Cola

http://russellbarthhasablog.wordpress.com/2014/06/21/marijuana-should-be-sold-to-kids-like-chocolate-or-cola/

LikeLike

I think we should focus on discrimination AGAINST drug users, not stigmatization OF drug users. This way we focus on the people and groups who violate the rights of drug users, NOT the ‘shame’ and ‘spoiled identity’ drug users are forced to take on by those who discriminate against them

LikeLike

Great point Russell I agree

LikeLike

Of the following excerpt from the article, I would have added “market related issues such as quality control, dosage standardization (for dosage dependent drugs), production […]”

FTA:

“Regulations instead should be confined to market related issues such as production, distribution, sale and advertising and seek to protect the rights and freedom of the individual.”

LikeLike

apologies for the delay – nice point – thank you!

Amended 🙂

LikeLike

While I agree it would be a welcome step in the right direction, decriminalisation is a dangerous half way measure that must quickly be superseded by legal regulation.

Most of the harms around drugs are caused not by the drugs themselves but by the consequences of a criminal market.

The only route to a rational policy on cannabis is a commercial market. Home growing will rapidly become an esoteric hobby just like home brewing and winemaking.

LikeLike

I think the police and law enforcement create considerable harm and tough enforcement and that fuels harsher and more violent criminal activities. I appreciate the harm caused by the criminal underworld but I think the damage from the state is at least comparable. So I think it’s crucial through decriminalisation to secure the all important right to possess/consume what you choose without criminalization threat or punishment. But I agree regulation is an important next immediate step, a two teir system allowing the individual personal possession and personal cultivation.

LikeLike